In October 2005 Texas prosecutors charged Brandon Dale Woodruff — then a 19-year-old freshman at Abilene Christian University — with murdering his parents Dennis and Norma. Unable to make the $1 million bail he sat in Hunt County Jail for more than three years awaiting trial. When the case finally was presented to a Greenville jury in northeast Texas the prosecution essentially posited during the 12-day trial that Brandon Woodruff was living a double life based on lies who ditched classes at ACU for gay adventures in wild Dallas. Faced with flunking out and returning home to a hick town the prosecutors argued that Brandon killed his disappointed parents for their life insurance so he would be free to pursue his gay life with carefree abandon. On March 20, 2009 the jury convicted Brandon Woodruff after only five hours of deliberation. The state earlier had waived the death penalty, and he automatically was sentenced to a life term behind bars.

The evidence introduced at trial on Brandon’s homosexuality and his coming out process was so prejudicial that the state prosecutors might as well have just called him the talented Mr. Ripley, and the jury might as well have just convicted him for being gay. Immediately after the conviction his defense counsel Katherine Ferguson told gay paper Dallas Voice in a March 26, 2009 article that in prosecuting Brandon Woodruff the state deployed a “strategy to highlight his sexual orientation,” and Ferguson had argued to the jury that prosecutors were equating “gay” with “murderer.” Ferguson further told the Dallas Voice:

“They certainly wanted to ram that point down the jury’s throat every moment they could,” Ferguson told Dallas Voice this week. “They were hoping that this would be a small-town East Texas jury, and they would be so blinded by that issue that they would not sit back and examine the facts of the case. My whole attitude was, I didn’t really care who he slept with. My concern was, did he murder his parents? And could the state prove it beyond a reasonable doubt? And I don’t feel the state did, but obviously the jury disagreed.”

An appeals court affirmed Brandon’s conviction notwithstanding the weak evidence. Indeed, during the appeals hearing, a panel judge expressly told state prosecutors “there are a lot of things that we are concerned with.” Woodruff currently is challenging his conviction through a writ of habeus corpus in federal court, and a legal memorandum filed with that court advises that Brandon’s innocence is supported by two lie detector tests:

After Mr. Woodruff exhausted his appellate rights, Eric Holden, one of the most respected polygraph examiners in the nation, administered a polygraph examination on whether Mr. Woodruff murdered his parents. Mr. Woodruff denied that he killed his parents and the test indicated his response was truthful. To further corroborate this result a different polygrapher re-examined Mr. Woodruff on the same question and Mr. Woodruff again showed to be truthful. According to studies addressing the reliability of polygraph examinations the chances of two properly conducted polygraph examinations both erroneously showing a truthful response are less than two-percent.

Brandon Woodruff’s federal challenge to his murder conviction has been pending now for nearly two years.

Dennis and Norma Woodruff were murdered on October 16, 2005 in their double-wide trailer in Royce City in Hunt County. No doubt it was a gruesome crime. The pair were sitting together on a sofa before the television set on a Sunday night, and both had been shot and stabbed multiple times. As described by state prosecutors in their appellate memorandum Dennis “died from a lethal gun shot wound to his face and nine fatal stab wounds to his face, neck, and chest, some as much as five inches deep,” and Norma’s “death was caused by five lethal gun shot wounds to the body, including four to her face and neck, and one defensive wound to her right hand, as well as a four inch stab wound across her neck.” When investigators came upon the crime scene two days later on October 18 their bodies and the sofa were blood soaked. The television was on, and Dennis still held in his hand a chewing tobacco spit cup.

The murdered couple had grown up in Texarkana, Arkansas, and met during the 1970s at Arkansas High School where both were in the band. Texarkana is the heart of the Bible belt. Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee in his preacher years headed the Beech Street First Baptist Church, and Texarkana’s sister town over the border in Texas is home to the American Baptist Association. The Woodruffs belonged to the evangelical Church of Christ. The two married in 1981 a year after high school graduation, and they both attended Southern Arkansas University.

After college the couple settled in Heath, TX in Rockwall County outside Dallas where Dennis was a quality control engineer and Norma was a certified public accountant. Their daughter Charla was born in 1985, and Brandon in 1986. The Woodruffs were religious folks, and Brandon attended church camp during summer where he met his best friend who later became his freshman-year roommate at Abilene Christian University. Dennis was not a sports fan but a big fan of Dolly Parton, Cher, Tina Turner and Bette Midler. Indeed, Dennis was obsessive about Dolly, and had collected her memorabilia since fourteen. The family frequently attended Dolly concerts and took trips to Dollywood. The couple had moved to the manufactured home in Royce City only a month before their murders, and still were in the process of moving out their personal items from the Heath home which they intended to list for rent. The downsizing move was to save money since they had accumulated some debt and were putting two children through college.

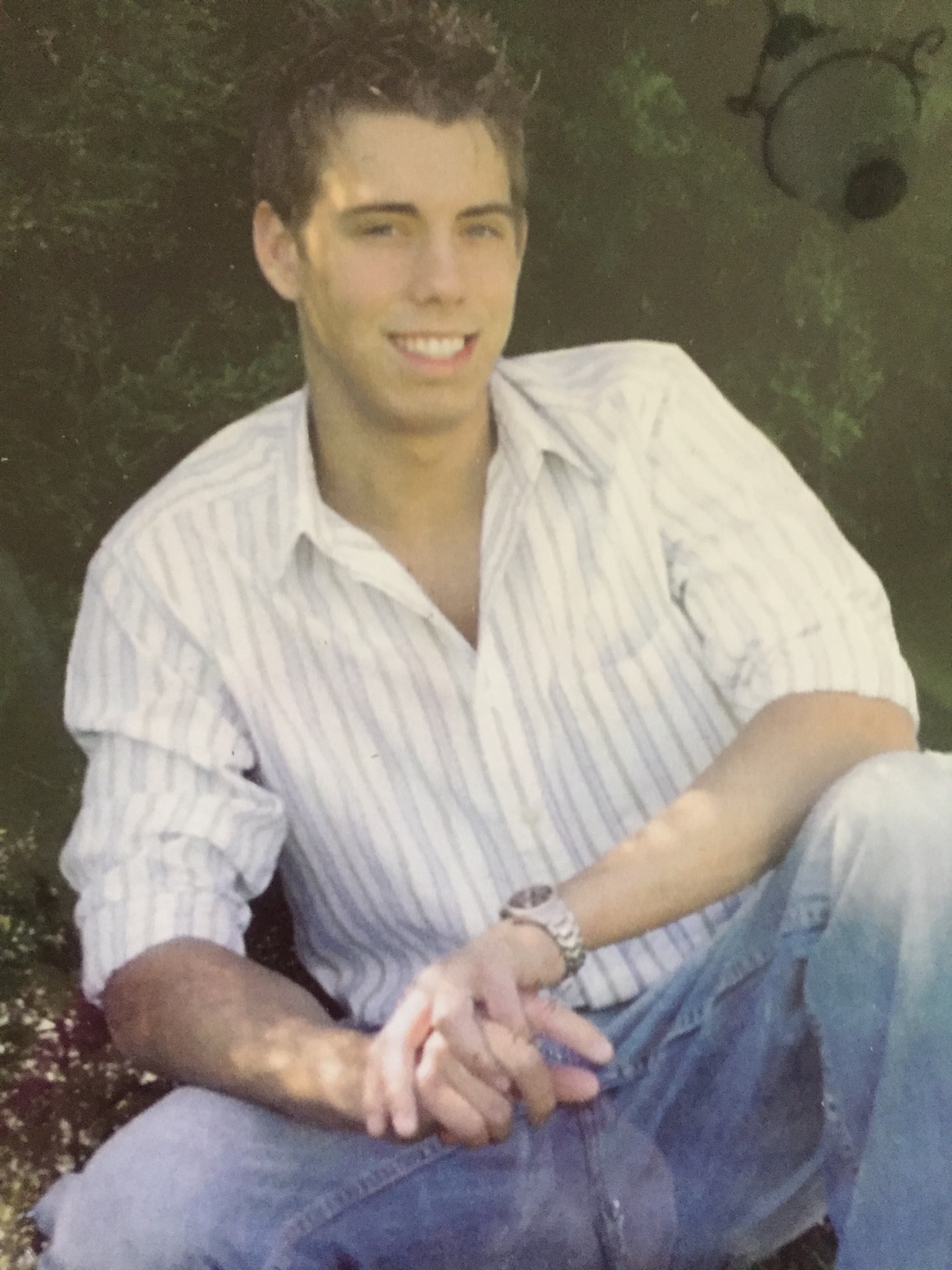

Brandon was charismatic and well-liked, and friends described him as “fun-loving” and “a great guy.” In his senior year of high school Brandon was voted with the most school spirit, and at college participated in the Freshman Follies. His passion was raising animals including show horses which was a pursuit also shared by both his mother Norma and sister Charla. In high school he was president of Future Farmers of America, and at ACU was enrolled as an agribusiness major.

However, the boy had little interest in academics. ACU accepted him only on a conditional basis, and from the start he was on probation. The college is governed by a Board of Trustees from the Churches of Christ, and among the many rules students are required to attend chapel services daily, not have sex and respect an 11:00 pm curfew. Homosexuality is incompatible with the ACU mission, and to this day the university refuses to allow a gay student group. ACU President Phil Schubert has said the university’s position for “faculty, staff and students” is clear in that “sex is reserved for the marriage bond between one man and one woman,” and “we do not believe homosexual behavior is condoned in the Bible.”

Obviously, ACU and Brandon were not a good match. Brandon was ditching classes and flunking out, and further was violating the school’s many rules. Unbeknownst to his ACU friends Brandon was involved with the Dallas gay scene. Heck, the strapping young man even did some porn work.

Brandon Woodruff was arrested on October 24, 2005 notwithstanding that law enforcement had no direct evidence tying him to his parents’ murders. There were no eyewitnesses. The gun and the knife had not been found. And investigators incredibly did not find any gunshot residue or any blood on Brandon or his clothing. According to the state’s theory Brandon murdered his parents and cleaned up all evidence tying him to the crime within a 45-minute period. Frankly, few professional hit teams could proceed so efficiently to erase all physical traces of their involvement with such a messy scene.

The criminal case against Brandon Woodruff was marred by constitutional violations and investigative blunders from the beginning. For example, the Hunt County District Attorney’s Office had ordered jailhouse recordings of Brandon’s conversations with his defense lawyer from which the DA’s office took notes. Upon learning of the recordings and notes the presiding judge ruled Brandon’s Sixth Amendment rights were violated, and suppressed the use of information learned from them. The DA’s Office recused itself, and special counsel from the Attorney General’s office took over the prosecution. However, the trial judge refused to dismiss the criminal indictment against Brandon Woodruff, and the Sixth Amendment constitutional violations are the principal issue in his federal challenge to the state conviction.

Further disturbing is the slipshod investigation into the murders. At the time of Brandon’s arrest in October 2005 investigators had not found the gun or knife used to kill his parents. Two-and-a-half years later in June 2008 as the trial date was approaching one of Brandon’s aunts discovered a Renaissance fair-style dagger in the barn at the Heath residence in a box of family possessions. Lab testing identified a single drop of his father’s blood under a skull on the handle, and prosecutors insisted they finally had direct evidence linking the boy to the horrible crimes.

Except not so fast. There are multiple issues casting substantial doubt on whether that dagger was one of the two murder weapons.

First, there was no clear indication that the dagger even belonged to or otherwise was ever possessed by Brandon, and a family member insisted it was part of a collection belonging to Brandon’s father.

Second, investigators previously had searched the barn right after the murders, and did not find the dagger. The excuse for not earlier finding it was because the Woodruff barn had been used by the family for storage, and was so packed that investigators simply were overwhelmed. Hardly inspires confidence, and it’s a shame that with such a horrible crime the investigating team was not more meticulous in their search efforts in the first instance particularly since an innocent man may have been convicted. The barn was kept unlocked, and anybody could have planted the dagger there after Brandon’s arrest.

Third, the dagger had only a single drop of blood from his father, and none from his mother. Any suggestion that Brandon otherwise wiped the dagger clean before storing it in the family barn seems specious; after all, he hardly was schooled in evidence elimination as part of a clean-up crew. Given that the crime scene was a blood bath and the knife used was deeply plunged multiple times into the murdered couple, one would have expected more incriminating evidence from the dagger if it in fact were the murder weapon. There are innumerable scenarios under which a drop of Dennis Woodruff’s blood could have ended up on the dagger even if it did belong to Brandon. For example, perhaps he cut himself packing it in preparing for the move from the Heath home to Royce City.

Fourth, the medical examiner testifying for the state could not conclusively establish that the dagger was the murder weapon but only “possible” based on the stab wounds to the two victims. And the defense expert more emphatically concluded “it is not consistent with the weapon.”

Finally, why the hell would Brandon store the dagger in the family barn which would be among the first places searched by law enforcement? Indeed, to this day the gun still has not been found, and prosecutors theorized that Brandon ditched it in Lake Ray Hubbard. So why ditch one murder weapon in a deep lake and store the other in a family barn? It’s simply illogical that Brandon would dispose the gun in one fashion and the dagger in another if he in fact used it to kill his parents.

The government only had circumstantial evidence — rather attenuated at that — against Brandon Woodruff, and the question begged is why would the 19-year-old kill his parents? This was a Herculean task for the state prosecutors to answer given that Brandon and his folks by all accounts had a loving relationship, and his arrest was a complete shock to the community. The state contended that Brandon Woodruff “murdered his parents because he was a troubled young man who had been living too many lies for too long,” and the central “lie” he supposedly perpetuated was his double life as a gay man.

As a general matter “evidence of a defendant’s homosexuality is not admissible if the defendant’s sexual orientation is not an issue” due to its prejudicial effect, and “courts reviewing the admission of prejudicial evidence of a defendant’s homosexuality . . . should weigh heavily the prevalence of anti-gay biases among judges and juries in determining whether to declare a mistrial or reverse a conviction” according to the legal treatise Sexual Orientation and the Law by the Harvard Law Review Association. For example, the Montana Supreme Court expressly recognized in its 1996 decision State v. Ford that “there will be, on virtually every jury, people who would find the lifestyle and sexual preferences of a homosexual or bisexual person offensive,” and accordingly held “our criminal justice system must take the necessary precautions to assure that people are convicted based on evidence of guilt, and not on the basis of some inflammatory personal trait.”

Such concerns about the prejudicial impact of Brandon’s homosexuality were particularly acute given that he was standing trial before a conservative East Texas jury in the heart of the Bible belt. Indeed, out of the fourteen (including two alternate) jurors chosen to judge Brandon, eight of them “feel or believe that being homosexual or gay is morally wrong” according to the voir dire during the selection process. Would it be acceptable to impanel eight avowed white supremacists in a criminal trial involving a black defendant? And yet eight Texans who by their own admission viewed homosexuals as morally inferior to heterosexuals were allowed onto the jury panel to judge a gay boy.

The prosecution argued that because Brandon Woodruff was not out to all his old friends he was living a “double life” which evidenced a deceitful side. Indeed, on appeal the state compared the “truth vs. fiction” about Brandon Woodruff, and citing record evidence expressly stated:

Before the Summer of 2005, the Appellant [Brandon] dressed like a cowboy; trained horses; and dated Morgan, his high school girlfriend. Starting that Summer, the Appellant began dying his hair; wearing Armani clothes; claiming he was a model; and partying with and dating gay Dallas men. His Dallas friends did not know about his old Rockwall life and his family and high school friends did not know about his new gay lifestyle.

The state took issue that once in college Brandon had developed a “new gay lifestyle” in Dallas, and as a 19-year-old freshman had not yet shared that knowledge with his old friends. Brandon’s coming out process was no different than it is for countless young gay men who often confide to family members and old friends only after first comfortably finding their own place in the gay world. In fact, months prior to the double murder, Brandon already had told his father he was gay. For prosecutors to argue that Brandon had a character flaw for not yet revealing his homosexuality to everyone necessarily prejudiced him before the jury which did not have a high opinion of homosexuals to begin with.

The trial record tangibly demonstrates that the homophobic “double life” argument was a successful tactic in prejudically turning minds against Brandon Woodruff. For example, a boyhood friend originally told the Texas Rangers who investigated the case that he did not believe Brandon was capable of murder. However, the investigators flipped his opinion by disclosing that Brandon liked guys. At trial state prosecutors asked this boyhood friend “would it be fair to say that the Brandon you thought you knew was not the Brandon you knew” to which he answered “yes.” And then they immediately followed up with the question “is it fair to say that your opinion that you expressed to the Rangers back in November of 2005 as to his capability of doing this has changed?” An objection from defense counsel was sustained which precluded an answer but the question was left hanging before the jury which exposed the homophobic game state prosecutors were cynical playing.

Incredibly, the state prosecutors mischaracterized Brandon’s tiered coming out process as “fiction versus truth” with sinister connotations, and to support the dubious conviction on appeal went so far to argue that this double life was evidence of his supposed motivation for the gruesome murders after creeping “reality” encroached upon his “fantasy world”:

He knew that his parents would not be around to disapprove or otherwise interfere with his life. Maybe he felt that with them dead he would not have to hide his gay lifestyle any more.

There simply is no evidence that Brandon Woodruff was compelled to kill his parents in order to live openly as a gay man. The cockamamie theory posited by state prosecutors that Brandon Woodruff was so conflicted that he felt only by getting rid of his unsupportive parents could he liberate himself from closet hell not only is a homophobic narrative but not supported by the factual record. The truth is that Brandon had an independent streak, and he certainly did not need his parents’ blessing in order to be openly gay. Heck, Brandon was hitting the gay clubs in Dallas since he was sixteen, and one press account reported that his mother Norma once confided to a family friend that she had become “exasperated” that “her son had become increasingly defiant in his late teens.” Brandon hardly sounds like a momma’s boy at her apron strings, and no doubt he was going to live his life the way he wanted regardless of whether it disappointed his parents’ Christian beliefs.

The prosecution further contended that Brandon killed his parents for their life insurance in order to embrace his gay life and avoid returning home. “He’s cashing in” state prosecutors argued before the jury, and “he’s killed his parents and he is starting a new life.” Sure, he may have been flunking out of college and maxing out his credit cards — how many kids does that describe? — but no doubt Brandon would land on his feet in gay Dallas with or without financial support from his parents. Brandon Woodruff had found an appreciative crowd in the big city where he danced at gay clubs and performed in adult films. If Brandon Woodruff were as money-obsessed as the state prosecutors insisted then that cute twink easily could have found himself a sugar daddy who’d put him up on short notice, and accordingly, it’s absurd as argued by the prosecution that he killed his parents in order to collect a payday in order to be gay. Heck, Brandon knew that his parents were financially struggling, and prior to their murders it’s unclear whether he even was aware they had life insurance which turned out to be only a modest amount.

The weak evidence upon which Brandon Woodruff was convicted is troublesome in its own right but the homophobic narrative which characterized the purported motivation suggests that a fundamental injustice may have occurred. In 2003 the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case Lawrence v. Texas struck down the sodomy statute but perhaps people still are getting convicted just for being gay in the Lone Star State.

Once production is finished on this film, the distribution information will be uploaded.